WRITTEN BY David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger

Executive Summary

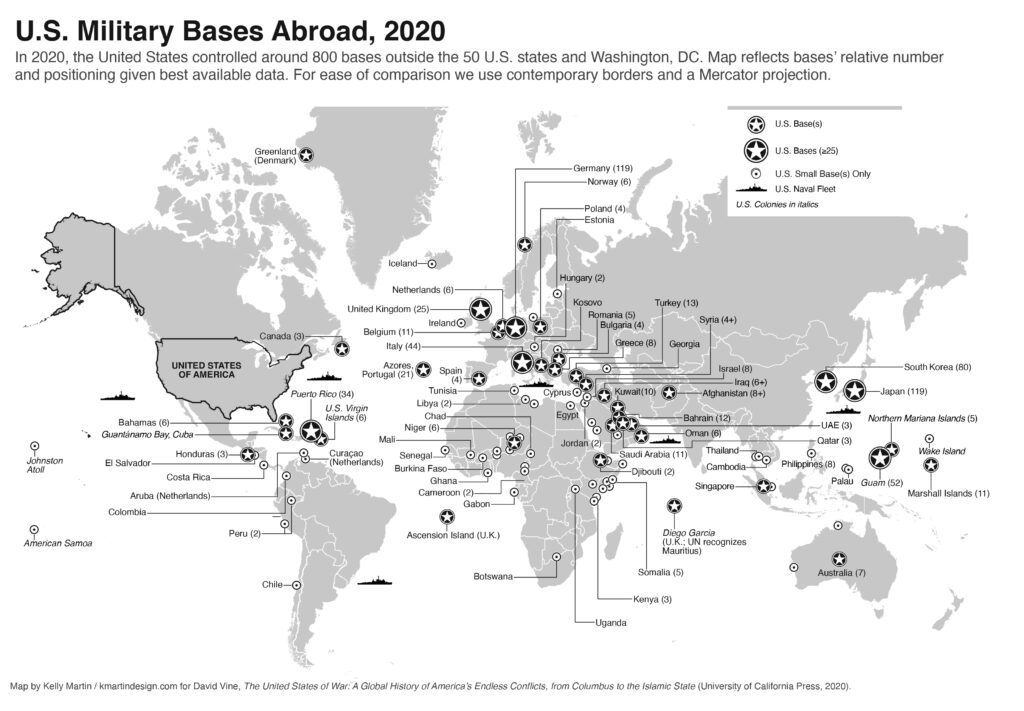

Despite the withdrawal of U.S. military bases and troops from Afghanistan, the United States continues to maintain around 750 military bases abroad in 80 foreign countries and colonies (territories). These bases are costly in a number of ways: financially, politically, socially, and environmentally. U.S. bases in foreign lands often raise geopolitical tensions, support undemocratic regimes, and serve as a recruiting tool for militant groups opposed to the U.S. presence and the governments its presence bolsters. In other cases, foreign bases are being used and have made it easier for the United States to launch and execute disastrous wars, including those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, and Libya. Across the political spectrum and even within the U.S. military there is growing recognition that many overseas bases should have been closed decades ago, but bureaucratic inertia and misguided political interests have kept them open.

Amid an ongoing “Global Posture Review,” the Biden administration has a historic opportunity to close hundreds of unnecessary military bases abroad and improve national and international security in the process.

The Pentagon, since Fiscal Year 2018, has failed to publish its previously annual list of U.S. bases abroad. As far as we know, this brief presents the fullest public accounting of U.S. bases and military outposts worldwide. The lists and map included in this report illustrate the many problems associated with these overseas bases, offering a tool that can help policymakers plan urgently needed base closures.

Fast facts on overseas U.S. military outposts

• There are approximately 750 U.S. military base sites abroad in 80 foreign countries and colonies.

• The United States has nearly three times as many bases abroad (750) as U.S. embassies, consulates, and missions worldwide (276).

• While there are approximately half as many installations as at the Cold War’s end, U.S. bases have spread to twice as many countries and colonies (from 40 to 80) in the same time, with large concentrations of facilities in the Middle East, East Asia, parts of Europe, and Africa.

• The United States has at least three times as many overseas bases as all other countries combined.

• U.S. bases abroad cost taxpayers an estimated $55 billion annually.

• Construction of military infrastructure abroad has cost taxpayers at least $70 billion since 2000, and could total well over $100 billion.

• Bases abroad have helped the United States launch wars and other combat operations in at least 25 countries since 2001.

• U.S. installations are found in at least 38 non-democratic countries and colonies.

Research and writing for this brief was supported by World BEYOND War and American University.

The problem of U.S. military bases abroad

During World War II and the early days of the Cold War, the United States built an unprecedented system of military bases in foreign lands. Three decades after the Cold War’s end, there are still 119 base sites in Germany and another 119 in Japan, according to the Pentagon. In South Korea there are 73. Other U.S. bases dot the planet from Aruba to Australia, Kenya to Qatar, Romania to Singapore, and beyond.

We estimate that the United States currently maintains approximately 750 base sites in 80 foreign countries and colonies (territories). This estimate comes from what we believe to be the most comprehensive lists of U.S. military bases abroad available (see Appendix). Between fiscal years 1976 and 2018, the Pentagon published an annual list of bases that was notable for its errors and omissions; since 2018, the Pentagon has failed to release a list. We built our lists around the 2018 report, David Vine’s 2021 publicly available list of bases abroad, and reliable news and other reports.1

Across the political spectrum and even within the U.S. military there is growing recognition that many U.S. bases abroad should have closed decades ago. “I think we have too much infrastructure overseas,” the highest-ranking officer in the U.S. military, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Mark Milley, acknowledged during public remarks in December 2020. “Is every one of those [bases] absolutely positively necessary for the defense of the United States?” Milley called for “a hard, hard look” at bases abroad, noting that many are “derivative of where World War II ended.”2

Across the political spectrum and even within the U.S. military there is growing recognition that many U.S. bases abroad should have closed decades ago.

To put the 750 U.S. military bases abroad in perspective, there are nearly three times as many military base sites as there are U.S. embassies, consulates, and missions worldwide — 276.3 And they comprise more than three times the number of overseas bases held by all other militaries combined. The United Kingdom reportedly has 145 foreign base sites.4 The rest of the world’s militaries combined likely control 50–75 more, including Russia’s two to three dozen foreign bases and China’s five (plus bases in Tibet).5

The cost of building, operating, and maintaining U.S. military bases abroad is estimated at $55 billion annually (fiscal year 2021).6 Stationing troops and civilian personnel at bases abroad is significantly more expensive than maintaining them at domestic bases: $10,000–$40,000 more per person per year on average.7 Adding the costs of personnel stationed abroad drives the total cost of overseas bases to around $80 billion or more.8 These are conservative estimates, given the difficulty of piecing together the hidden costs.

In terms of military construction spending alone — funds appropriated to build and expand bases overseas — the U.S. government spent between $70 billion and $182 billion between fiscal years 2000 and 2021. The spending range is so broad because Congress appropriated $132 billion in these years for military construction at “unspecified locations” worldwide, in addition to $34 billion clearly spent overseas. This budgeting practice makes it impossible to assess how much of this classified spending went to building and expanding bases overseas. A conservative estimate of 15 percent would yield an additional $20 billion, although a majority of the “unspecified locations” could be overseas. $16 billion more appeared in “emergency” war budgets.9

Beyond their fiscal costs, and somewhat counterintuitively, bases abroad undermine security in a number of ways. The presence of U.S. bases overseas often raises geopolitical tensions, provokes widespread antipathy toward the United States, and serves as a recruiting tool for militant groups like al Qaeda.10

Foreign bases also have made it easier for the United States to become involved in numerous aggressive wars of choice, from the wars in Vietnam and Southeast Asia to 20 years of “forever war” since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. Since 1980, U.S. bases in the greater Middle East have been used at least 25 times to launch wars or other combat actions in at least 15 countries in that region alone. Since 2001, the U.S. military has been involved in combat in at least 25 countries worldwide.11

Foreign bases also have made it easier for the United States to become involved in numerous aggressive wars of choice, from the wars in Vietnam and Southeast Asia to 20 years of “forever war” since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.

While some have claimed since the Cold War that overseas bases help spread democracy, the opposite often appears to be the case. U.S. installations are found in at least 19 authoritarian countries, eight semi-authoritarian countries, and 11 colonies (see Appendix). In these cases, U.S. bases provide de facto support for undemocratic and often repressive regimes such as those that govern in Turkey, Niger, Honduras, and the Persian Gulf states. Relatedly, bases in the remaining U.S. colonies — the U.S. “territories” of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands — have helped perpetuate their colonial relationship with the rest of the United States and their peoples’ second class U.S. citizenship.12

As the “Significant Environmental Damage” column in Table 1 of the Appendix indicates, many of the base sites abroad have a record of damaging local environments through toxic leaks, accidents, the dumping of hazardous waste, base construction, and training involving hazardous materials. At these overseas bases, the Pentagon generally does not abide by U.S. environmental standards and frequently operates under Status of Forces Agreements that allow the military to evade host nation environmental laws as well.13

Given such environmental damage alone and the simple fact of a foreign military occupying sovereign land, it is unsurprising that bases abroad generate opposition almost everywhere they are found (see “Protest” column in Table 1). Deadly accidents and crimes committed by U.S. military personnel at overseas installations, including rapes and murders, usually without local justice or accountability, also generate understandable protest and damage the reputation of the United States.

Listing the bases

The Pentagon has long failed to provide adequate information for Congress and the public to evaluate overseas bases and troop deployments — a major facet of U.S. foreign policy. Current oversight mechanisms are inadequate for the Congress and the public to exercise proper civilian control over the military’s installations and activities overseas. For example, when four soldiers died in combat in Niger in 2017, many members of Congress were shocked to learn that there were approximately 1,000 military personnel in that country.14 Overseas bases are difficult to close once established, often due mainly to bureaucratic inertia.15 The default position by military officials seems to be that if an overseas base exists, it must be beneficial. Congress rarely forces the military to analyze or demonstrate the national security benefits of bases abroad.

The default position by military officials seems to be that if an overseas base exists, it must be beneficial.

Beginning in at least 1976, Congress began to require the Pentagon to produce an annual accounting of its “military bases, installations, and facilities,” including their number and size.16 Until Fiscal Year 2018, the Pentagon produced and published an annual report in accordance with U.S. law.17 Even when it produced this report, the Pentagon provided incomplete or inaccurate data, failing to document dozens of well-known installations.18 For example, the Pentagon has long claimed it has only one base in Africa — in Djibouti. But research shows that there are now around 40 installations of varying sizes on the continent; one military official acknowledged 46 installations in 2017.19

It is possible that the Pentagon does not know the true number of installations abroad. Tellingly, a recent U.S. Army-funded study of U.S. bases relied on David Vine’s 2015 list of bases, rather than the Pentagon’s list.20

This brief is part of an effort to increase transparency and enable better oversight of Pentagon activities and spending, contributing to critical efforts to eliminate wasteful military expenditures and offset the negative externalities of U.S. bases abroad. The sheer number of bases and the secrecy and lack of transparency of the base network make a complete list impossible; the Pentagon’s recent failure to release a Base Structure Report makes an accurate list even more difficult than in prior years. As noted above, our methodology relies on the 2018 Base Structure Report and reliable primary and secondary sources; these are compiled in David Vine’s 2021 data set on “U.S. Military Bases Abroad, 1776-2021.”

What’s a “base”?

The first step in creating a list of bases abroad is defining what constitutes a “base.” Definitions are ultimately political and often politically sensitive. Frequently the Pentagon and U.S. government, as well as host nations, seek to portray a U.S. base presence as “not a U.S. base” to avoid the perception that the United States is infringing on host nation sovereignty (which, in fact, it is). To avoid these debates as much as possible, we use the Pentagon’s Fiscal Year 2018 Base Structure Report (BSR) and its term “base site” as the starting point for our lists. Use of this term means that in some cases an installation generally referred to as a single base, such as Aviano Air Base in Italy, actually consists of multiple base sites — in Aviano’s case, at least eight. Counting each base site makes sense because sites with the same name are often in geographically disparate locations. For example, Aviano’s eight sites are in different parts of the municipality of Aviano. Generally, too, each base site reflects distinct congressional appropriations of taxpayer funds. This explains why some base names or locations appear several times on the detailed list linked in the Appendix.

Bases range in size from city-sized installations with tens of thousands of military personnel and family members to small radar and surveillance installations, drone airfields, and even a few military cemeteries. The Pentagon’s BSR says that it has just 30 “large installations” abroad. Some may suggest that our count of 750 base sites abroad is thus an exaggeration of the extent of U.S. overseas infrastructure. However, the BSR’s fine print shows that the Pentagon defines “small” as having a reported value of up to $1.015 billion.21 Moreover, the inclusion of even the smallest base sites offsets installations not included on our lists due to the secrecy surrounding many bases abroad. Thus, we describe our total of “approximately 750” as a best estimate.

It is possible that the Pentagon does not know the true number of installations abroad. Tellingly, a recent U.S. Army-funded study of U.S. bases relied on David Vine’s 2015 list of bases, rather than the Pentagon’s list.

We include bases in U.S. colonies (territories) in the count of bases abroad because these places lack full democratic incorporation into the United States. The Pentagon also classifies these locations as “overseas.” (Washington, D.C. lacks full democratic rights, but given that it is the nation’s capital, we consider Washington bases domestic.)

Closing bases

Closing overseas bases is politically easy compared to closing domestic installations. Unlike the Base Realignment and Closure process for facilities in the United States, Congress does not need to be involved in overseas closures. Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush closed hundreds of unnecessary bases in Europe and Asia in the 1990s and 2000s. The Trump administration closed some bases in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. President Biden has made a good start by withdrawing U.S. forces from bases in Afghanistan. Our previous estimates, as recently as 2020, were that the United States held 800 bases abroad (see Map 1). Due to recent closures, we have recalculated and revised downward to 750.

President Biden has announced an ongoing “Global Posture Review” and committed his administration to ensuring that the deployment of U.S. military forces around the world is “appropriately aligned with our foreign policy and national security priorities.”22 Thus, the Biden administration has a historic opportunity to close hundreds of additional unnecessary military bases abroad and improve national and international security in the process. In contrast to former President Donald Trump’s hasty withdrawal of bases and troops from Syria and his attempt to punish Germany by removing installations there, President Biden can close bases carefully and responsibly, reassuring allies while saving vast sums of taxpayer money.

For parochial reasons alone, members of Congress should support closing installations overseas to return thousands of personnel and family members — and their paychecks — to their districts and states. There is well-documented excess capacity for returning troops and families at domestic bases.23

The Biden administration should heed growing demands across the political spectrum to close overseas bases and pursue a strategy of drawing down the U.S. military posture abroad, bringing troops home, and building up the country’s diplomatic posture and alliances.

Source: https://quincyinst.org/report/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/